Smart moo-ve

Michael Cooper

DateJanuary 2022

How lab-grown meat can help the climate crisis

The carbon cost of meat

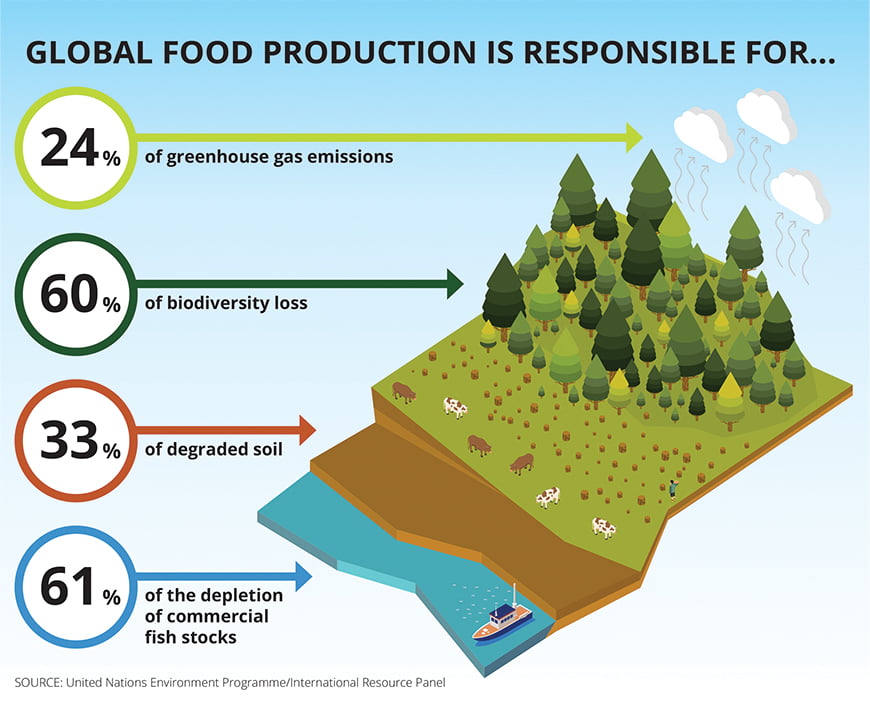

It’s a well-established fact that the carbon footprint of the global food industry is vast. Recent estimates suggest what we eat is responsible for one third of all human-driven greenhouse gas emissions across the planet.

Food production generates approximately 17,300,000,000 metric tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions every year, a figure that will only rise with global population numbers. This enormous quantity is predominantly the result of the machinery used in processing, fertilizers, transportation, and storage. To place the figure into context, it is higher than the emissions of every country in the world, barring those of the two largest global emitters – China and the U.S.

The single largest contributor to this colossal amount is livestock. Cows require lots of space, and as such more than half of the world’s cropland produces feed for livestock, as opposed to plants for human consumption.

Grazing land for ruminants takes up more than a quarter of the world’s ice-free land surface, and approximately 100 million hectares of land is used to grow crops for livestock globally. Most commonly, the land set aside for grazing was originally forest and was cleared before use, at the cost of millions of carbon-sequestering trees.

The production of plant-based food accounts for approximately 29% of emissions – by comparison, the use of animals in the food chain is estimated to cause twice that, with the likes of cows and pigs responsible for approximately 57% of all food production emissions. Cows alone account for almost as many emissions as all plant-based foods , due to the disconcerting fact that a solitary kilo of beef generates 70kg of greenhouse gas emissions.

New research conducted by the renowned journal Nature assessed the global impact of food production and suggested measures to abate the crisis. It proposed that a move towards a meat-free diet was vital to keep climate change under 2°C , let alone 1.5°C. In real terms, this means the average person should eat 75% less beef, 90% less pork and 50% fewer eggs; achieving this would halve emissions from livestock. In western countries, however, the changes required are even more dramatic, with Nature suggesting that westerners must cut beef consumption by 90% to hit the target.

An effective solution to this problem would be for us all to become vegan (or at least vegetarian); doing so would make tremendous strides in the battle against the climate crisis. But it’s not that simple.

It’s not easy eating greens

Prior to our modern understanding of the environmental impacts of a meat-eating society, vegetarians were already citing health, ethical, religious or economic reasons as their reason for having wholly plant-based diets.

Estimates on the global percentage of vegetarians and vegans differ markedly from study to study, however it is widely accepted that fewer than one in five people don’t eat meat. The world’s most vegetarian country is India, with an estimated 20% to 39% of its 270 million people at least vegetarian, primarily for religious reasons. At the other end of the scale, over 98% of the Spanish and Portuguese are meat eaters. In the U.S., a series of Gallup polls over a twenty-year period has seen the figures for veganism creep slowly from a mere 2% of the population to 3%.

Whatever the reasons, the world is a long way off the removal of meat from our collective dinner plates. But if people are unwilling to stop eating meat, the answer could be to change how we come by it. The answer could be synthetic meat, and it’s heading for your refrigerator faster than you think.

No longer paddock to plate?

Synthetic meat (aka cultured or clean meat) is created in a five-step process.

- Muscle tissue is harmlessly obtained from a live animal.

- Stem cells are extracted from the tissue and left to grow into muscle cells.

- Muscle cells are grown on ‘biological scaffolding’ to form muscle tissue.

- Muscle fibres proliferate in a bioreactor.

- Muscle fibres are processed to form meat, ready for the dinner plate.

A single stem cell extracted from a cow is sufficient to produce one trillion muscle cells. That means a 5000-litre bioreactor could feasibly meet the protein requirements of 2000 people for a year.

The research and development of laboratory-grown meat really took off in 2013, when a team led by Professor Mark Post of Maastricht University successfully produced the world’s first beef burger using stem cells extracted from cows. The cost of this solitary patty was estimated to have been around $300,000, however, and the race has been on to drive the price down ever since.

An independent study undertaken around this time found Professor Post’s model of lab-grown beef would potentially use 45% less energy than the average global figures for farming cattle. It would also produce 96% fewer greenhouse gas emissions and required an astonishing 99% less land. These early developments in synthetic meat also proved growing meat without the animal would remove the need for potentially harmful antibiotics and hormones in the final product. An impressive start for the sector.

Some five years later, U.S. manufacturer Memphis Meats announced they had produced a quarter pound of beef for a mere $600. With the prospect of a profitable production cost in sight, dozens of companies joined the race, and in 2021, Future Meat Technologies announced the production of chicken breast for a mere $7.70 per pound.

At this point, major supermarket chains started to sit up and take notice, and off the back of their exciting progress, Future Meat raised $347m in investment, meaning their work could gain even more momentum. Last year the company launched the world’s first synthetic meat production line in Rehovot, Israel, and is now expanding into the United States.

Future Meat’s founder, Professor Yaakov Nahmias, claims the commercial advantage his company holds in the race is through the use of stainless-steel fermenters to remove waste generated by tissue cells in order to support the growth of animal cells. Nahimas contends this is a more robust method and much more efficient than competitors who use stem cells, recycling over 70% of the nutrients.

Late last year, San Francisco-based Eat Just’s stem cell-based chicken became the first synthetic meat product to receive marketing approval when it was certified for sale in Singapore.

Forecasting the curve

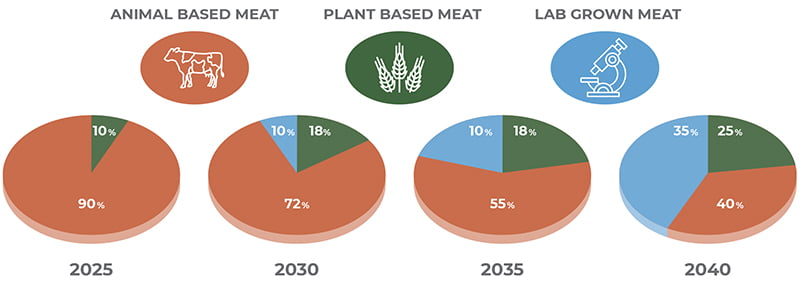

A 2020 study by Statistica provided forecasts on the breakdown of market share between meat, plant-based meat replacement and synthetic/cultured meat in coming years. In it, they gave the clear message that synthetic meat is only heading in one direction.

If this prediction is to come true, it would mean in less than a generation, more than one-third of the meat consumed globally will be grown in laboratories. Our leaders and governments clearly have a huge task ahead of them in terms of transitioning the millions of people whose livelihoods depend on the current status quo.

Whether it is Future Meat, Eat Just or any of the other rising players that wins the race to dominate the sector, one thing is for sure: the days of raising animals to be slaughtered and eaten are numbered.

No bull.

Share This