Science in the Corridor

Carbon Neutral

DateSeptember 2021

New research reveals the ins and outs of old-field recovery

Dr Tina Parkhurst from the Harry Butler Institute at Murdoch University has just published a new paper in the Journal of Ecological Solutions and Evidence investigating how plants recover on ex-agricultural land similar to our reforestation projects.

In the early 1900s, more than 90% of the native vegetation in the West Australian wheatbelt was cleared for agriculture. These woodlands and shrublands were dominated by a Eucalyptus loxophleba overstory, a vegetation community that is now listed as threatened.

The remaining 10% of vegetation is patchy and fragmented, making poor habitat for the region’s rich biodiversity and unique wildlife. The removal of native vegetation has also created salinity and water issues that make the land less suitable to farming.

Consequently, restoration of these ex-farmland areas is crucial to protecting biodiversity and providing other ecosystem services, such as carbon sequestration.

No easy feat

It’s widely understood that there’s a number of barriers to achieving ecosystem recovery on old-fields. These thresholds can be due to both living factors like altered seed banks and also non-living factors like the soil’s chemical make up.

In revegetated fields, the leaf litter and woody debris needed for some wildlife can be slower to develop, or even missing altogether. Native seed availability can also be affected by reduced soil seed banks and seedling predation by ants or pests.

Research into how these ecosystems recover guides best practice for ecological restoration to make it more effective in the future, particularly as restoration is needed at large-scales across the globe.

A comparative approach

Tina’s research, completed with Assoc/Prof Rachel Standish (Murdoch University) and Dr Suzanne Prober (CSIRO), wanted to find out how revegetated sites compared to undisturbed native reference sites and fallow croplands where no restoration action has taken place.

The revegetated sites have been subject to planting using active restoration interventions 10 years ago with the aim of being as close as possible to the native areas. Today, revegetation methods have improved thanks to research like this, and many more native species are part of the planting mix.

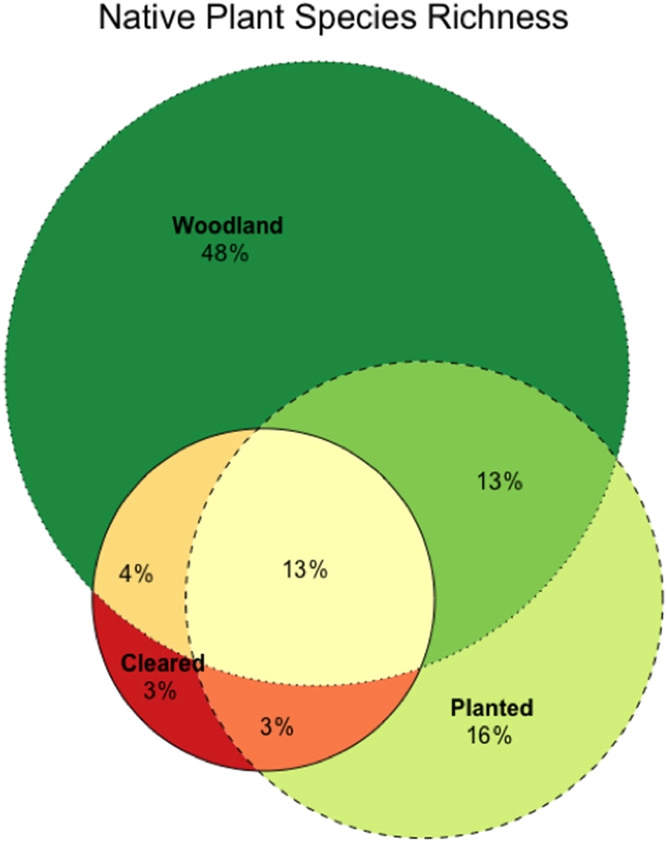

The team measured and compared a range of different aspects of the vegetation communities across the three states. They wanted to know how native species, exotic species, and soil conditions were different and what may be causing any differences.

Restoration in action

The revegetated old fields were all in a stage of transition toward the native reference state. Plant species richness, diversity, woody debris, and leaf litter were all higher in the revegetated areas compared to the croplands, but hadn’t quite reached the levels of the undisturbed areas yet.

Another positive finding was that exotic species were lower in the revegetated areas compared to the croplands. Herbaceous species however showed weaker signs of recovery, thought possibly to be due to the soil chemical legacy from agriculture or altered seed banks.

Next steps

Finding out how to better restore herbaceous species will be an important area of future research, as will tracking the recovery of these ecosystems over the next 10 years and beyond.

Dr Parkhurst’s other research has been finding out how bird and invertebrate species are recovering in these areas, along with more analysis of soil physio-chemical properties.

The full research paper can be found here.

Parkhurst, T., Prober, S. M., & Standish, R. J. (2021). Recovery of woody but not herbaceous native flora 10 years post old-field restoration. Ecological Solutions and Evidence, 2:e12097. https://doi.org/10.1002/2688-8319.12097

Share This